Pica: Symptoms, Causes, and Therapy Options

Contents

Introduction

Pica is a type of eating disorder characterized by the persistent consumption of non-nutritive, non-food substances for at least one month. These substances may include items such as dirt, clay, chalk, hair, paper, or ice. The condition is named after the Latin word for magpie, a bird known for its indiscriminate eating habits. Pica can occur in individuals of any age but is more commonly observed in children, pregnant women, and individuals with developmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or intellectual disabilities.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), Pica is classified under Feeding and Eating Disorders and is considered a serious condition because it can lead to severe health complications, including poisoning, infections, and gastrointestinal issues. This article will explore Pica, focusing on the Symptoms, Causes, and various Therapy Options available for effective treatment.

Common Symptoms of Pica

The symptoms of Pica involve the recurrent consumption of non-food items. Below is a table outlining the common symptoms of Pica and examples of how they may manifest in daily life:

| Symptom | Description/Example |

|---|---|

| Consumption of Non-Food Substances | Repeatedly eating substances that are not typically considered food, such as dirt, clay, hair, chalk, or ice. For example, a child may eat pieces of chalk during class. |

| Health Problems Related to Ingesting Harmful Substances | Experiencing medical complications such as lead poisoning, intestinal blockages, or infections due to consuming harmful non-food items. For example, an individual may suffer from anemia after consistently eating clay. |

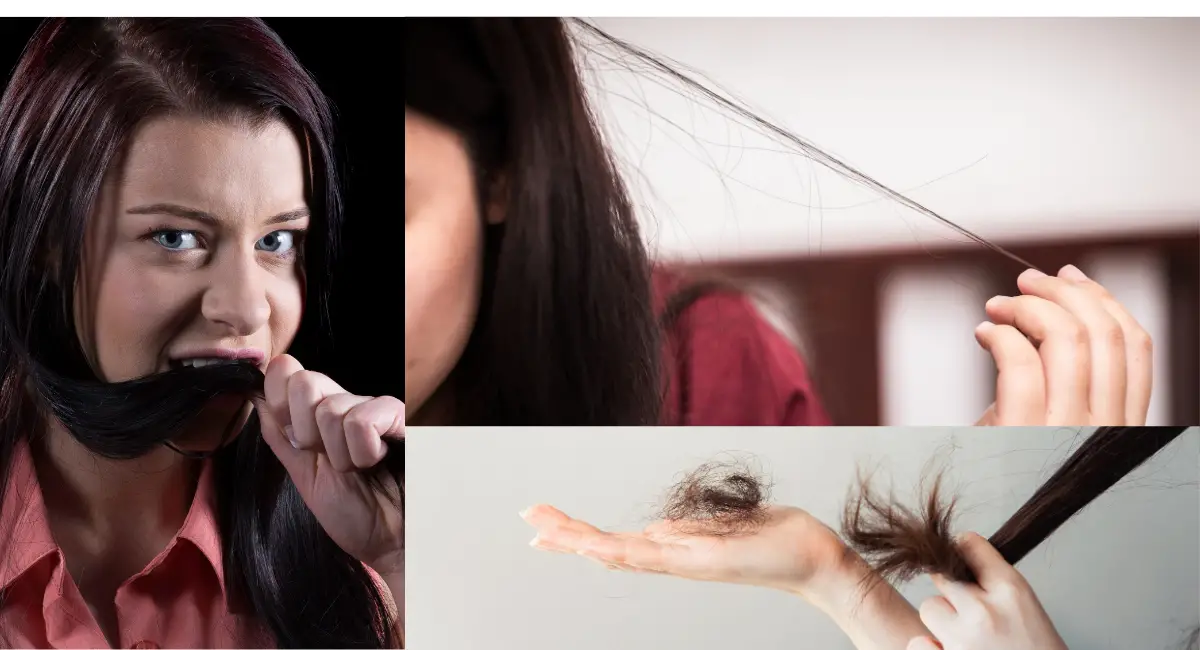

| Gastrointestinal Issues | Eating non-food substances can lead to digestive issues such as stomach pain, constipation, or intestinal blockages. For example, an individual who eats hair may develop a hairball in their stomach, causing abdominal discomfort. |

| Persistent Cravings | Having strong and recurring cravings to consume non-food substances despite knowing the potential health risks. For example, someone may feel an overwhelming urge to eat dirt, even though they understand it can be harmful. |

| Dental Damage | Repeatedly chewing or eating hard substances like stones or glass can cause damage to the teeth, such as chipping or erosion of the enamel. For example, a person who chews on ice constantly may experience dental issues over time. |

Causes and Risk Factors of Pica

The exact cause of Pica is unknown, but the disorder is believed to result from a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Below are key causes and risk factors associated with the development of Pica:

1. Nutritional Deficiencies

One of the most common explanations for Pica is a nutritional deficiency, particularly in minerals such as iron or zinc. Individuals with nutrient deficiencies may develop Pica as an instinctive response to address these deficiencies by consuming non-food substances.

- Iron deficiency anemia is strongly associated with Pica, particularly the craving for ice, dirt, or clay. In some cases, the body’s attempt to restore mineral balance can lead to the ingestion of non-nutritive substances.

- Zinc deficiency has also been linked to Pica, as this mineral is essential for proper taste perception and appetite regulation.

John, a 30-year-old man with iron deficiency anemia, has developed a craving for eating ice, a behavior known as pagophagia, which is a form of Pica. After receiving treatment for his anemia, his cravings for ice diminish.

2. Developmental and Psychological Factors

Individuals with developmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or intellectual disabilities, are at an increased risk of developing Pica. These individuals may engage in non-food consumption due to sensory sensitivities, curiosity, or a lack of awareness of the dangers of eating non-food items.

- Pica is more prevalent in children and individuals with developmental disorders who may explore their environment by tasting or eating non-food substances.

- Psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, or trauma may also contribute to the onset of Pica. For some individuals, eating non-food substances may serve as a coping mechanism or a way to self-soothe during periods of emotional distress.

Emma, a 5-year-old girl with autism, frequently eats small pieces of paper and cardboard. Her therapist works with her family to address her sensory processing issues and redirect her behavior toward safer, more appropriate items.

3. Cultural and Environmental Factors

In certain cultures, the consumption of non-food substances may be part of traditional practices or beliefs. For example, eating clay or dirt, known as geophagia, is practiced in some regions of Africa and the southern United States, particularly among pregnant women. Environmental factors, such as poverty and food insecurity, may also increase the risk of Pica, as individuals may consume non-food items when nutritious food is unavailable.

- Cultural practices that involve the consumption of non-food substances are often linked to beliefs about their health benefits or spiritual significance. For example, in some cultures, consuming clay is believed to aid digestion or prevent nausea during pregnancy.

- Food insecurity may also play a role in Pica behaviors, as individuals in impoverished or resource-limited environments may turn to non-food substances when access to nutritious food is scarce.

Sarah, a pregnant woman living in a rural community where geophagia is common, regularly eats clay, believing it will help alleviate her nausea. However, she later develops anemia and gastrointestinal issues due to the clay’s interference with nutrient absorption.

Therapy and Treatment Options for Pica

Treating Pica requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses the underlying causes of the disorder, whether they are nutritional, psychological, or environmental. Below are key treatment options:

1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective treatments for Pica, especially when the behavior is linked to psychological factors or habits. CBT helps individuals identify and change negative thought patterns and behaviors related to the consumption of non-food substances.

John works with a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) therapist to better understand and identify the patterns underlying his habit of ice eating. Through their sessions, John learns to recognize the triggers and emotional factors that prompt his urge to chew on ice.

2. Nutritional Therapy

For individuals with Pica caused by nutritional deficiencies, Nutritional Therapy is essential for correcting the underlying issue. This treatment involves addressing iron, zinc, or other deficiencies through dietary changes or supplementation to reduce cravings for non-food substances.

After being diagnosed with iron deficiency, Sarah’s doctor prescribes her a daily regimen of iron supplements and offers detailed dietary recommendations to help boost her iron intake. These recommendations include incorporating iron-rich foods into her diet, such as lean meats, leafy green vegetables, beans, and fortified cereals.

3. Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral Interventions are particularly effective for individuals with developmental disorders or children who engage in Pica. These interventions involve reinforcing positive behaviors, teaching individuals about the dangers of eating non-food items, and redirecting their attention to safer alternatives.

Emma’s therapist uses Behavioral Interventions to assist her family in teaching her to engage in safe and appropriate play with sensory toys as an alternative to her habit of eating paper. The therapist works with the family to implement structured strategies, focusing on the use of positive reinforcement to encourage and reward Emma when she refrains from engaging in Pica behaviors.

Long-Term Management of Pica

Long-term management of Pica requires ongoing therapy, monitoring, and lifestyle changes to prevent the recurrence of harmful behaviors. Below are key strategies for long-term management:

- Consistent Therapy: Regular participation in CBT or Behavioral Interventions helps individuals address their underlying motivations for eating non-food substances and maintain healthier behaviors.

- Nutritional Monitoring: For individuals with Pica related to nutritional deficiencies, ongoing monitoring of nutrient levels and regular check-ups with a healthcare provider ensure that cravings do not return as deficiencies are corrected.

- Safe Environment: Creating a safe environment, particularly for children and individuals with developmental disorders, can reduce the risk of exposure to non-food substances. This may involve child-proofing areas or removing hazardous items that may be ingested.

- Support Networks: Engaging with support groups or mental health professionals provides emotional and psychological support, helping individuals stay on track with their recovery and manage stress or anxiety that may trigger Pica behaviors.

Conclusion

Pica is a serious eating disorder characterized by the persistent consumption of non-food substances. While it can affect individuals of all ages, it is particularly prevalent among children, pregnant women, and individuals with developmental or intellectual disabilities. The disorder can lead to significant health complications, including poisoning, infections, and gastrointestinal issues. However, with effective treatments—such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Nutritional Therapy, and Behavioral Interventions—individuals can overcome the urge to consume non-food substances and improve their overall health. Long-term management strategies, including consistent therapy, nutritional monitoring, and the creation of a safe environment, are essential for preventing relapse and maintaining recovery.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Young, S. L., & Wilson, M. J. (2012). A review of the geophagia literature and the multiple health impacts of earth-eating. PLOS ONE, 7(3), e30545.

- Kettaneh, A., Eclache, V., Fain, O., Sontag, C., Uzan, M., & Stirnemann, J. (2005). Pica and food craving in patients with iron-deficiency anemia: A case-control study in France. The American Journal of Medicine, 118(2), 185-188.

- Williams, D. E., Kirkpatrick-Sanchez, S., & Burd, L. (2006). Pica in individuals with developmental disabilities. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 48(5), 367-371.

- Rose, E. A., Porcerelli, J. H., & Neale, A. V. (2000). Pica: Common but commonly missed. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 13(5), 353-358.

Explore Other Mental Health Issues